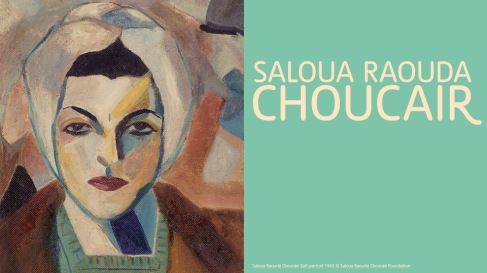

Little known outside her native country of Lebanon, Salouda Raouda Choucair is an artist born in 1916 whose work is the subject of an exhibition at the Tate Modern that places her rightfully as one of the pioneers of abstract art.

It’s also a very important exhibition to witness for another reason. This exhibit is the first in the Tate’s 13 year history to be dedicated to a solo artist who has rarely been seen or known of outside the Middle East since the 1950s. This marks a courageous step for the gallery, from being an institution that deals exclusively with already well established artists towards a gallery that not only presents us with what we know but pushes the boundaries of what to expect, in this case in respect to the art in non-western regions of the world.

Some 120 pieces, paintings and installations, are currently housed in four rooms, in what can only be described as a very intense exhibit. The most astonishing thing about Choucair’s works is their diversity. It would be understandable if upon seeing them, one were to think they were witnessing a collection by many different artists. She is an expert manipulator of style and form.

At the time that Choucair began her tutelage under the leading Lebanese artists Mustafa Farroukh and Omar Onsi, impressionist and realist styles were in favour in Lebanon. The self-portrait, one of her earliest works on display, was created during this period and the influence of the times can be clearly seen in it. However, making this piece a poster for their Salouda Raouda Choucair exhibition, Tate Modern has done her a disservice as they have chosen the least representative of all her works to represent her. Indeed, walking into the first room, the self-portrait, although expertly executed is dwarfed and overshadowed by Choucair’s other paintings which are heading in a completely contrary direction to it.

Room 1

An interesting aspect of her paintings is the fact that although very different styles can be seen, from her nude paintings to the abstract, they were not transitional. One style did not develop into another, instead she worked in many styles during the same period, exploring and experimenting in many directions. In a sense, she is the ultimate free artist in that she never bound herself to any one style or school. She did as she pleased and she did it with great skill. Perhaps this was due to the fact that her art was not tied to her financial survival. She led a happy life within her family and did not need to brand herself in order to sell her works, so her art was dictated by nothing other than her intellectual ambitions.

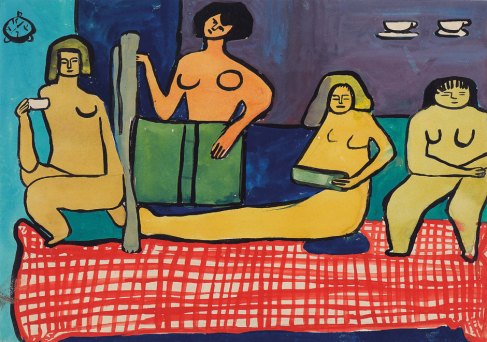

As seen through western eyes, Choucair’s works can seem inherently western. After all, in 1948 she did leave her native Lebanon and travel to Paris for three years where she studied drawing, mural painting, sculpting and engraving at the prestigious Ecole Nationale Superieure des Beaux- Arts. It was here where she encountered abstract modernism and met/became the pupil of the cubist, figurative painter Fernand Leger. Indeed, the domestic scenes she portrays in Les Peintres Celebres are likely to be based around Leger’s Le Grand Dejeuner.

In fact, many of her paintings in this room bear a resemblance to those of western artists such as Ben Nicholson, Joseph Albers and Ellsworth Kelly can all be considered to have similar elements. Whilst it would be true that there are elements of Western modernist styles and techniques, even to Choucair herself, suggesting that her work represents western ideals would be to miss the point entirely.

In 1943, Choucair had taken a trip to Cairo where she fell in love with Islamic art and architecture filled, as they are, with geometric patterns, calligraphic scripts and structural features. If looked at with a more discerning eye and with the awareness of Middle Eastern history, the Islamic, and perhaps more importantly, the Arabic influence and sovereignty in her work becomes apparent. Abstraction lies at the heart of Choucair’s work and it is working within this realm that she is not turning to modern western values in art but rather returning and embracing the traditional and historic Middle Eastern values of non-representational, geometric and mathematical beauty.

Representational art as the foundation from which all modern and experimental artworks diverged is a foreign concept in Middle Eastern art, whose convention lies in abstraction and for which to create representational art would have been the ultimate divergence.

If another look is taken at Les Peintres Celebres series, it is possible to see the geometric shapes the nudes conform to. Choucair has turned figurative painting on its head and instead of using shapes to portray figures, she uses figures to emphasis shapes and patterns that evoke designs often found in Arabic script and Islamic art.

Les Peintes Celebres (1948-9) © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

Untitled (1948-9) © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

Abstract paintings in Gouache done during the same period as the more figurative designs © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

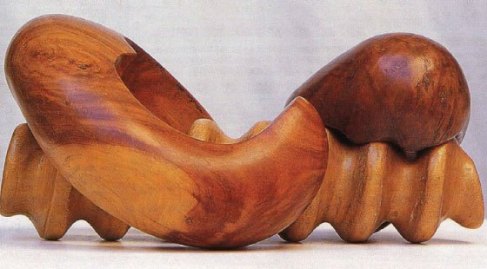

In the middle of the first room of the exhibition stands a piece unlike any that surround it. A wooden carved sculpture is simultaneously our first indication as well as her first venture into where she was heading in a mid and later career. In this piece can be seen the architectural elements that are found in Islamic buildings as well as the ideas of eternity prominent in Sufi poetry. The curvature of the lines is reminiscent of the infinity sign and creates a sensuous introduction into the next room.

Room 2

Choucair’ s painting’s developed in the late 1940s into what she termed “Fractional Modules”, which indicate her interest and study of algebraic geometry with its emphasis on plane curves and line intersections. These elements can be clearly seen in her oil painting Composition in Blue Module 1947-51

Composition in Blue Module (1947-51) © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

Rhythmical Composition in Yellow (1952-5) © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

It’s possible to mistake Choucair’s Rhythmical Composition in Yellow (also in the second room) as a piece by artists such as Jean Arp, Robert Delauney, Juan Gris, László_Moholy-Nagy, EL Lissitzky or Alexander Vesnin

This is deceptive as this painting is another circumstance where one can compare it to artists reaching the same destination from opposing directions. The jagged lines, block forms and colours can simultaneously be described as Western as well as Middle Eastern

In the second room of the exhibition, we predominantly see the continuation of Choucair’s inevitable progression into the realm of sculpture. After a brief stint in America, where she studied enamelling techniques and jewellery making, Choucair returned to Beirut in the early 1950s to concentrate on executing her ideas in three dimensional forms.

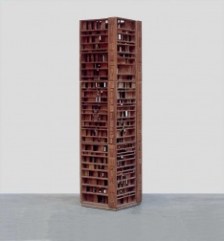

The potential infinite trajectory and variability of the line was the focal point of her earliest sculptural series. One such example is her Sculpture with One Thousand Pieces 1966-8

Sculpture with One Thousand Pieces 1966-8© Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

This piece seems simple upon first viewing, but a greater understanding and appreciation of the intricate craftsmanship that was needed for its creation develops on closer examination. The block houses intricately carved and highly complex internal forms as perplexing as the ancient puzzle balls of China. These forms, taken together, indicate a possible infinite pattern that extends beyond the visible material world.

However, this piece is not only interesting as an art piece but also as an insight into the life of the artist. The assistant curator of the exhibition, Ann Coxon, informs us that this piece along with all of Choucair’s sculptural works, were either put to use or strewn about the artist’s house. This one in particular was used as a lamp, with a light bulb being placed inside it. The gallery’s decision to not include the light bulb was an understandably difficult one as either way, something would have been lost. As it currently is, we are deprived of being able to view the piece as it was used by the artist herself, and so lose the personal touch. However, although it would have been interesting to see, we are given the original intellectual intention of the work unfettered by any overt personal elements, which may have been considered irrelevant by Choucair.

The stress on the irrelevancy of the artist and any political/personal interpretations of her works is admirable. She is not a confessional artist. She is not here to sell her ego, nor is she interested in the transient and limiting politics that surround her. She works on a purely intellectual basis, a realm that values mathematical and scientific principles above arbitrary or subjective notions of identity and politics.

This room also showcases Choucair’s experimentation with materials, ideas and her fascination with the forms of Sufi poetry. One of the defining characteristics of Sufi poetry, be it Rumi, Hafiz or Farid ud-Din, is the fact that each stanza of a poem may stand alone or be taken as part of a whole, and so it is with Choucair’s sculptural series entitled Poems. The flexibility and variability of these pieces work in the same manner, their parts may be taken individually or as a whole. They are intended to be interactive, however in order to last the exhibition, people are asked not to move them.

One of the series called Infinite Structure 1963-5 consists of twelve rectangular stone blocks that may be piled on top of each other, taken apart and arranged in any manner. It was made in part as an homage to Constantin Brancusi’s (1876–1957) project Endless Column, version1 1918 (now at MoMA, NY) but with the carved geometric flavour of Islamic interrelated forms. Choucair considered each block to have its own unique character, while still forming part of the whole. The photo below shows it grouped respectively into 4 and 8 pieces but this is a decision the curator had to make in presenting it. It is possible to have it displayed a number of ways and the point of the piece is that it is changeable, it is fluid with many possibilities, it is infinite yet it’s one piece and yet also one of a series.

Infinite Structure (1963-5) © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

Another series, Duals, plays with the idea of interaction, balance and harmony. The artist uses wood, stone and silver to create forms of intimate embraces. These sculptures also consist of more than one part but unlike the poem series, the parts in Duals cannot stand alone, they need their partners to complete them.

The Screw (1975-7) © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

The screw is carved out of wood of three different colours and consists of three interlocking parts that can only be fitted together in one particular way in order to complete the piece. This work, perhaps unintentionally, resembles a set of human lungs and can be considered a metaphor for human connections and the idea that life can only exist in an interconnected manner

The Screw dismantled (1975-7) © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

In this room, the versatility of Choucair’s craftsmanship can be seen as she also worked in plastic, metal and was one of the first to experiment with fibreglass in sculptural form.

Room 3

The third room of the exhibition fastens around the belief that art and daily life ought to be linked. In a large display there can be seen various small maquettes that were created throughout Choucair’s career. There are models for public sculptures, fountains, park benches along with smaller items that are to be used in personal households such as jewellery and salt and pepper shakers. To Choucair there is no barrier between art and daily life, these two elements informed and complemented each other. In 1963, she was awarded the National Council of Tourism Prize for the execution of a stone sculpture for a public site in Beirut.

Above one of the displays is a painting entitled Two=One, a piece that again speaks to the infinite and of the connection between duality and unity. This work is significant for another reason; it is the first and only indication in her art of the context in which the artist was working. It is a modular piece from the 1940s which was pierced by shards of glass from Choucair’s apartment window when a bomb hit nearby during a bombing raid in the Lebanese civil war of 1980’s. Many holes and a piece of glass are still visible upon close inspection of the piece.

Two=One (1947-51) (complete with hole at its centre) © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

This is a piece more anthropological and archaeological in nature, in the sense that it tells us more about the artist and her life than it does her art. Unfortunately this piece is overshadowed by its historical experience, and I fear that it is appreciated more for what it’s been through than for its artistic elements.

This leads us to the astonishing pieces in the fourth and final room of the exhibition.

Room 4

You would be forgiven for thinking that you have stumbled into a very different exhibition upon entering this last room.

The sculptures in this room are made of acrylic and nylon wired, spun steel and glass and instantly take your mind to artists such as Barbara Hepworth in their sculptural abstraction. These masterpieces permeate with the Sufi sense of infinity, movement and the beauty of mathematics.

In one piece, Choucair uses one single piece of thread to emphasise the multi dimensional dynamic possibilities of curves and lines. This room also shows the artist’s continuing fascination with the possibility of sculpting with water. She designed fountain heads, such as Water lens, 1969-71, which led translucent streams of water to follow the “trajectory of the line” in a kinetic interplay between light and motion.

Waterlens 1969-71 © Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation

The 1980s and 1990s issued forth some recognition and awards for her work. In 1982, Choucair was commissioned to create a major public sculpture by the Lebanese Lions’ Club and further commissions followed including one which currently stands in the Gibran Khalil Gibran Garden in downtown Beirut. Then in 2011, the Beirut Exhibition centre held a major retrospective of her work.

The Tate’s decision to hold an exhibition of Choucair’s works is commendable, but this a recognition long overdue for an artist who has worked ceaselessly and innovatively for the best part of five decades, always keeping the visual potential of abstract intellectual ideas at the core of her work. Let’s hope this exhibit is an indication that the art world is catching up with this visionary and pioneering artist.

This exhibition runs from April 17–November 17, 1013, at the Tate Modern, London.

Admission £10 (£8.50 concessions)

Open 10am to 6pm every day and 10pm on Friday and Saturday.

http://www.tate.org.uk

020 7887 8888